Progressive overload is a fundamental principle in strength training and fitness, where you gradually increase the stress placed on your muscles to stimulate growth and adaptation. This can be achieved by increasing weight, reps, sets, training frequency, or intensity over time. The goal is to continually challenge the body, preventing plateaus and promoting strength, endurance, and muscle development. This is extremely important (and sometimes overlooked!) in our fitness routines. It is essentially how we progress whether we are beginners, seasoned fitness-veterans, or dealing with an injury or setback.

There are several ways to implement progressive overload: lifting heavier weights, performing more reps with the same weight, improving exercise form, or reducing rest time between sets. However, progression should be gradual to avoid injury and allow adequate recovery. Proper nutrition, sleep, and rest are also crucial to supporting muscle growth and adaptation!

Athletes* with regular workout schedules should be implementing this principle (i.e. increasing their lifts over time and not using the same weight for 3 reps as they do for their 10 rep max). It could also look like trying to run a faster mile-pace or hold a faster pace on the rower during workouts. However, this principle is EXTREMELY important in two other scenarios: postpartum return to exercise and exercising after an injury.

In both cases, the athlete needs to start light and slow to see the response on the body versus going from “zero to a hundred” in any given workout. Let’s look at a few practical examples:

- A new mom wants to get back to doing 20″ box jumps. First, she has to be able to move her body without impact – let’s say to squat and deadlift light to moderate weight (for her). Then, she would incorporate very low jumps over a line in the floor (and with rest between jumps). If she had no symptoms, she could progress to jumping on a 3-4″ plate and stepping off during a workout. If she had no symptoms, she could increase the height of the platform she was jumping on during workouts. If she did have symptoms, she would go back to the stage that did not generate symptoms and building strength and endurance there before trying to progress again in a few weeks.

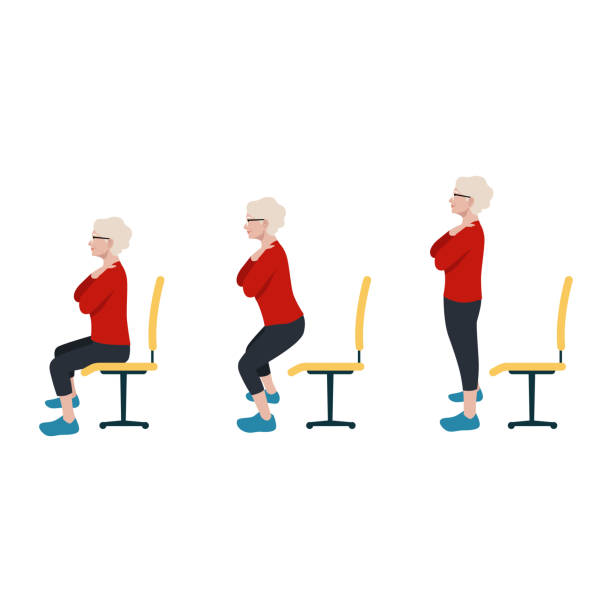

- A 60-year old athlete just had a knee replacement and wants to get back to back squatting with weight. Once they can walk around for 20-30 minutes without symptoms, they could begin by squatting to a box/bench above parallel (no additional weight). Once 3 sets of 10-15 reps can be performed there, we could lower the height of the box slightly to demand a little more range from the joint. Once that felt “easy”, we could add a small db or kettlebell to the same box squat. Then the athlete could work with a lower target (back to body weight only) AND/OR start adding more weight to the box squat to develop strength in the legs/core. Slowly and surely this athlete will be able to add range to the squat and weight to the squat over time.

In both cases above, there may be a stage that takes longer than others but the key is that over time, progression must be made. These progressions are exactly the same for athletes walking into a gym for the first time. We don’t start with a 1 rep max back squat, we start with squatting our body weight to a box or bench and progressing from there! In all cases, proper form in the movement is critical.

If we want to see our muscles grow and get stronger, we have to keep challenging them (and ourselves!). If you are wondering if there’s a next step for you to take in your own progressions, talk to your coach!

*every human is considered an athlete – we were built to move our bodies 😉